There are many, many rules laid out for putting on a perfect dinner party. You’ve got to have a great spread, naturally, with all sorts of exotic cuisine ready to be devoured by the eager participants. Fine wines and hard drinking is a plus too. Some even descend into lewder shenanigans if you live in certain suburbs and own enough lubricant.

But ask any PC gamer who was around at the beginning of the CD-ROM revolution and you’ll get one answer about what makes a perfect party. You’ve got to have a 7th Guest.

Sorry for the convoluted nature of the intro there, but when the thoughts strike in certain ways, you’ll get these things spewing out on the page every so often. So, where were we? Ah yes, The 7th Guest, one of the earliest and finest examples of that genre we so hatefully call the Interactive Movie.

Back in the early 1990s, games were being delivered on ever more ludicrous numbers of high density 3.5” floppy disks. Star Trek: Judgement Rites came on 11 and took 2 hours of decompressing to even install. Games needed more space and the CD-ROM revolution gave developers what they needed. However, they didn’t necessarily know what to do with this new found freedom.

“We’ve got loads of space, but most of our data isn’t actually that big,” they may have hypothetically thought. “How do we justify any hike in prices and the outlay on a rudimentary disc drive? Ah ha! Video!”

To an eager youth, the sight of full-motion video in games was an exciting thing to behold. Soon we would have the likes of Mark Hamill, Clive Owen, Christopher Walken, Dennis Hopper and even that guy who plays Q in Star Trek all adorning out puny 14” monitors in glorious Super VGA.

Unfortunately, most of these games were atrocious, barely interactive and full of terrible acting outside of the big stars roped in. There were some truffles to be sniffed out of the mud though, like the Wing Commander games, Gabriel Knight: The Beast Within and such, and of course The 7th Guest, a flick-screen horror/puzzler.

Set in a genuinely unnerving mansion house owned by the eccentric toymaker Henry Stauf, who invited 6 guests from the local community to his place and proceeded to make them disappear. Your task, as an unnamed person entering the house many years later, is to find out what happened to the 6 people who went missing and also to discover just who the mysterious 7th guest was.

You go about achieving these goals by doing exactly what you would in real life, which is by solving logic puzzles and playing draughts against an invisible opponent. Each time you solve a puzzle, a vision is played back in grainy FMV, showing what guests were doing in the rooms at the time of the party, developing the plot and filling you in on the story.

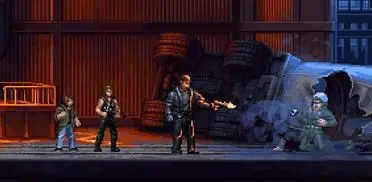

The importance of The 7th Guest isn’t in the precise quality of the game, just its position in gaming’s time line. Released at the very beginning of a new technological wave, it heralded the slow transition from cartoon-y graphics to more realistic visuals, bringing with it higher quality sound and a desire to emulate films.

It’s influence can still be felt today in things like Blue Toad Murder Files, just with more evil and ghostly women appearing in corridors. As a museum piece, it’s interesting to play in order to see just how far – or, indeed, how close we still are – we are from the effective fusion of games and films. Heavy Rain, for example, is just another in a long line of interactive movies.

It’s a very important game, historically, and while visually it’s very basic compared to what we can see nowadays, it’s worth tracking down a copy via whatever means you think are viable. Gaming changed forever when it was released and, thankfully, it was the last PC game I remember that was released at the 70 quid price point. Some things do change for the better, then.

One of the more fiendish puzzles involved swapping both sets of bishops over to the other side of the chess board

One of the more fiendish puzzles involved swapping both sets of bishops over to the other side of the chess board Not the most appetising dessert ever made, is it?

Not the most appetising dessert ever made, is it? The video bits might look rubbish now, but back in the day they were jaw-dropping

The video bits might look rubbish now, but back in the day they were jaw-dropping