If you haven’t heard about Headlander, here’s the short version: It’s a Metroidvania-style adventure set in a thoroughly groove-tastic 1970s vision of a sci-fi future, made by the folks at Double Fine. If that combination of gameplay style, setting, and developer speaks to you, then you should play Headlander.

That was enough to know that this was a game for me. The world of Headlander is positively groovy. It’s firmly inspired by the low-budget, countercultural sci-fi of the late 60s and early 70s, with film grain, technicolor filters, and a fine veneer of psychedelic imagery everywhere you look. It’s a got a little bit of OG Star Trek and a lot of Barbarella, filled with utopia-building robots showing off sexually liberated dance moves.

The story takes place in a future where humanity has disappeared, having had their minds transferred into robotic bodies. You, a disembodied head in a rocket-powered space helmet, are all that remains of flesh-and-blood mankind. Your lack of limbs grants you one notable advantage–you can vacuum off the heads any automaton you see and take control of its robotic body.

Those robotic bodies have their own abilities and there are areas only certain models can access, so you’ve got to explore the space colony in search of new bodies to inhabit, which in turn open up new areas to explore and new robots to control. It’s the formula that powered 2D entries in the Metroid and Castlevania franchises for years, and the same that brought to life excellent indie titles like Axiom Verge and Ori and the Blind Forest.

But Headlander is a bit more linear than any of those titles. There’s room to explore, hidden upgrades to find, and pathways to get lost in, but there’s always a clear objective pushing you forward and an obvious bottleneck between each major area. Most of the body-switching necessary to advance will have you seeking out security bots of various colors, with each hue representing another level of security clearance. Occasionally you’ll need to find a body with some unique ability to conquer certain puzzles, but those moments are fairly few.

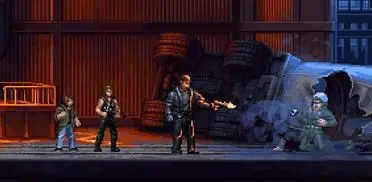

As you’re exploring, those same security bots you need to advance will also be shooting at you, and there’s a lot going on with Headlander’s combat. You’ve got gun-equipped humanoid bodies that can fire lasers and take cover, wall-mounted turrets, beam-firing minibosses, and ape-like burly bots that can beat the crap out of opponents. All those enemies will be trying to take you out, and you can take control of any of them to turn the tables. On top of that, your body-less head is solid in combat as well, ripping off robotic craniums with is vacuum ability, and spending points in the substantial upgrade tree will get you reflective shielding, charge attacks, and the ability to set headless enemies as helpful drones.

Despite all that, the combat isn’t particularly challenging or strategic. A big chunk of the upgrade tree just feels like wasted space, and I mostly forgot about my high-level ability upgrades since I never really needed them. I can’t say that I really want the combat to be harder, because as it stands it’s wildly chaotic, hard to make sense of, and the controls don’t have the precision you need in a difficult action game.

I’d say that Headlander is more a puzzle game than an action title, but there isn’t a whole lot of depth to the puzzles, either. Mostly you need to find the appropriately-colored guard to get through a color-coded security door. Sometimes you have to make a laser bounce along a series of pads. There’s a weird, out of nowhere Simon-like puzzle at the end of the game.

The part where Headlander is a video game is thin. The combat is weak, the puzzles are simplistic, and exploration rewards you with upgrades and abilities that give you advantages in fights that are already incredibly easy to win. Yet despite all that, I kind of loved my time with it. It’s just got so much style.

From the utopian ideals espoused by automated minds, to the soundtrack that bounces from oppressive, synth-heavy sci-fi sounds to funky disco beats, from the psychedelic rainbow explosions of technicolor to the soft southern accent of your guidesman, and from the booty-shaking robot dance moves to the layer of film grain that covers it all, it’s impossible not to admire Headlander’s devotion to its aesthetic, tone, and style.

Performance & Graphics

Minimum Requirements

- OS: Windows 7 64-bit

- Processor: Dual-core 2 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB RAM

- Graphics: AMD Radeon HD 7750

Recommended Requirements

- OS: Windows 7 64-bit

- Processor: Quad-core 3 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB RAM

- Graphics: Nvidia GeForce GTX 750 Ti

Those requirements aren’t exactly stringent, and Headlander’s good looks are a matter of its style rather than any impressive technical feats. You can expect fine performance on any modern gaming PC.

Additional Thoughts

It’s a cliche, but Headlander is far more than the sum of its parts. All its individual mechanics are solid, though not especially exciting, and if the game stretched itself out any further than its brief, five-hour time, those gameplay elements would quickly get very tiresome. For any other title, that would a damning criticism and a doomed sentence to mediocrity.

But if you have any love for the setting Headlander draws from–any at all–then you will love what those five hours give you. There’s so much life and personality to the game’s world and the hippie robots that populate it that the time spent there is a delight. The gameplay elements provide just enough of a structure to keep that time interesting, and there are few titles that can equal Headlander’s devotion to its own look and feel.

HEADLANDER VERDICT

While lackluster combat and simplistic puzzles would prove a damning criticism for most games of this type, Headlander’s tone and aesthetic is so fully-realized that the whole package manages to be a groovy, retro delight.

TOP GAME MOMENT

The first time you take control of a civilian robot and realize there’s a dedicated dance button.

Good vs Bad

- It’s super-groovy, man

- Look and feel is a perfectly-executed take on psychedelic sci-fi

- Exploration hooks provide just enough depth to keep things interesting

- Brief run time keeps it from overstaying its welcome

- Combat isn’t interesting

- Puzzles are very simple