Iconoclasts is a unique game in the sense of simultaneously being a fantastic example of how to develop games as an indie, and how not to develop games as an indie. The solo project by Joakim Sandberg, known also online as Konjak, is a beautiful, deep, fun, original, unique, captivating game with many aspects that would be lost or altered had a larger company been in charge, or even more people. It also took 10 years to finish, which by the developer’s account have, at times, been grueling.

Nonetheless, I’d say the result is definitely worthy of the effort the developer put into it. I’ll address actual concrete features as well, but it must be said that Iconoclasts has, lacking a better word, a “soul”. A sense of completeness that you’ll feel when playing games which had true passion and enthusiasm put into them. Don’t get me wrong, even in the biggest, most formulaic and generic AAA productions, there are definitely people on the dev team who are passionate about what they are doing, but some games are such pure works of creativity bubbling up from an eager developer that it rubs off on the end product.

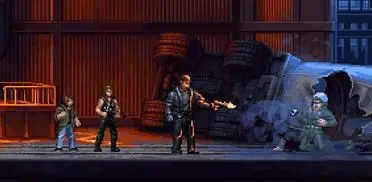

Iconoclasts is a pixel-art metroidvania with RPG elements. This particular arrangement of traits may not exactly be unique, especially these days with the archetype living a renaissance and every other indie dev putting out a similar game, but keep in mind that the idea for Iconoclasts is a decade old. It also happens to be an exemplar of its kind. Pixel-art, in these past years, has seen such a measure of use that some in the gaming community have knee-jerk negative reactions to it, but damn, Iconoclasts is masterclass is visuals. The colors pop, everything can be distinguished, paths and props can be differentiated from static props without it being jarring and the character art, backgrounds and vistas look fantastic.

The game starts off with pretty standard locations - foresty area, desert with crystals, underwater base - but as the game moves forward, you’ll enter some otherworldly settings many of which manage to innovate both in terms of mechanics used and visual cues. To achieve a unity of visuals, angles are used to great effect, with the square and cube shapes appearing in ways other than your standard pixellated visuals.

In terms of gameplay, Iconoclasts doesn’t exactly reinvent the wheel, but it does make for a really nice wheel. Our character, Robin, is equipped with a small gun and a very large wrench which are used to interact with the world around us. The various enemy types behave fairly differently, though it takes a while for the more unique ones to pop up from the assortment of mods sporting various permutations of different attacks and weak points we’ve seen before across the genre. Puzzles usually rely on the use of the wrench and platforming, though they do also mix in some of the effects of different ammo used for your weapon time to time.

Boss battles are well crafted both in terms of mechanics, offering a challenge without being unfair, and visuals, which up the spectacle. They feel sufficiently large and unlike regular enemies or encounters, and the art style evokes the old-greats of the franchise. Sometimes you’re required to hit weakpoints, sometimes you just need to wail at ‘em till they drop, at other times you cannot directly hurt them, but need to solve a puzzle mid-fight to open them up to damage.

In terms of story, Iconoclasts relies primarily on its characters. The world is interesting, begging to be dug into, but much of it is kept obscure, on purpose, to keep up an air of mystery. Much of the known world is governed by the One Concern, a totalitarian government founded on the religion of “Him”, their god-figure, whose earthly prophet is known as Mother. They assign people jobs, everything is rationed, and the chosen few who are allowed to work with machines powered by the rare and valuable Ivory are priest-like in stature.

The protagonist, Robin, is a rogue mechanic, meaning someone who knows how to fix stuff but isn’t sanctioned by the Concern, which is apparently a capital offense. The story is kicked off with agents coming to arrest her, and is propelled by her escape and meeting with the pirate Mina, who prefers leaping into action over planning. As the cast expands and the plot unfolds, players will find themselves in a non-formulaic, and best of all, not entirely predictable story.

At times, the game even places the player in control of these other characters. The first example of this is during a boss fight where Robin and Mina are trapped on two sides of a wall, and the player can switch between them at will, however at other times you control a different character exclusively. These are also the weakest elements of the game in terms of gameplay and progression. While the story does sometimes necessitate this, whenever playing as someone else it becomes apparent how much the underlying mechanics have been tailored with Robin, the character you control most of the time, in mind. These sections are not dealbreakers, and do add more than they detract due to the narrative content, but they are a low-point.

The game also features one of the less savory aspects of metroidvania games, namely, backtracking. Very early on in the game you’ll find objects you do not yet have the necessary ability or equipment to interact with, and it takes quite a while to actually acquire these. The upgrade system, which allows you to add a maximum of three minor stat boosting abilities, also doesn’t add much to the game, as these upgrades have minimal effects usually, and taking damage also takes them offline gradually, so often times at least one won’t even be active.

The game is also filled with interesting little touches. Very rarely does the protagonist speak, and usually the player gets to pick the answers which affect dialogue later on, but at one point when another character asks her her name, a small pixel-art picture of a Robin bird appears in the speech bubble instead of it being written out. People familiar with Konjak’s other works will also have a few easter eggs hidden for them - for example, Mina is a very blatant reference to one of his earlier projects, Mina the Pirate.

ICONOCLASTS VERDICT

Iconoclasts is a kind of game that no AAA studio could ever have made. It has all the mechanics, visuals and other easily judged elements that a video game needs, and nailed down really well too, but it also has a less tangible feel to it that just endears it to the player. Even among other nostalgic pixel-art metroidvania games, this one stands out, and ought to be remembered as one of the indie greats.

TOP GAME MOMENT

For the sake of avoiding spoilers I’ll be vague, but there is a particular part-gruesome, part-intriguing “the plot thickens” moment fairly early on in the game when a weird, white, Ivory infused plant sprouts from someone’s corpse. This happens right after a particularly fast-paced and very hectic boss-battle, and feels like the perfect narrative pay-off for the previous gameplay sequence. It’s also really creepy when you start to think about it.

Good vs Bad

- Fantastic art style

- Unique world

- Engaging gameplay

- Well written

- Side-character sections